Why does reporting out the results the work done in break out groups sometimes result complete buzz kill?

I have heard it said that reports from break out groups should be abolished since they are so often boring and do not provide enough depth to really benefit the work of the broad group. I agree wholeheartedly if:

The report out doesn’t fit the situation. Though report outs are incredibly important, they are not required in all circumstances. For example, if the small group work is supporting team building or is setting the stage for deeper work to come, there is not real need to report out the results. Or, if the small groups are developing input that will be reported out under a larger process – such as a public consultation report – there is no real place for report outs so their value is lost and unnecessary.

The objectives of the report out are not clear or the process is unstructured and poorly managed.

The report out process is dull and does not advance the group’s work or contribute to the achieving the outcomes the meetings is supposed to be achieving. How many times have you sat through a table by table report out that consists of either a catalog of everything the group discussed so that nothing anyone contributed is left out; or, the recitation of the personal views or experience of the group leader that does not bare much resemblance to what the group discussed.

Here are three dynamic techniques that avoid boredom and give report outs the chance to strengthen group learning and meeting outcomes:

Here are three dynamic techniques that avoid boredom and give report outs the chance to strengthen group learning and meeting outcomes:

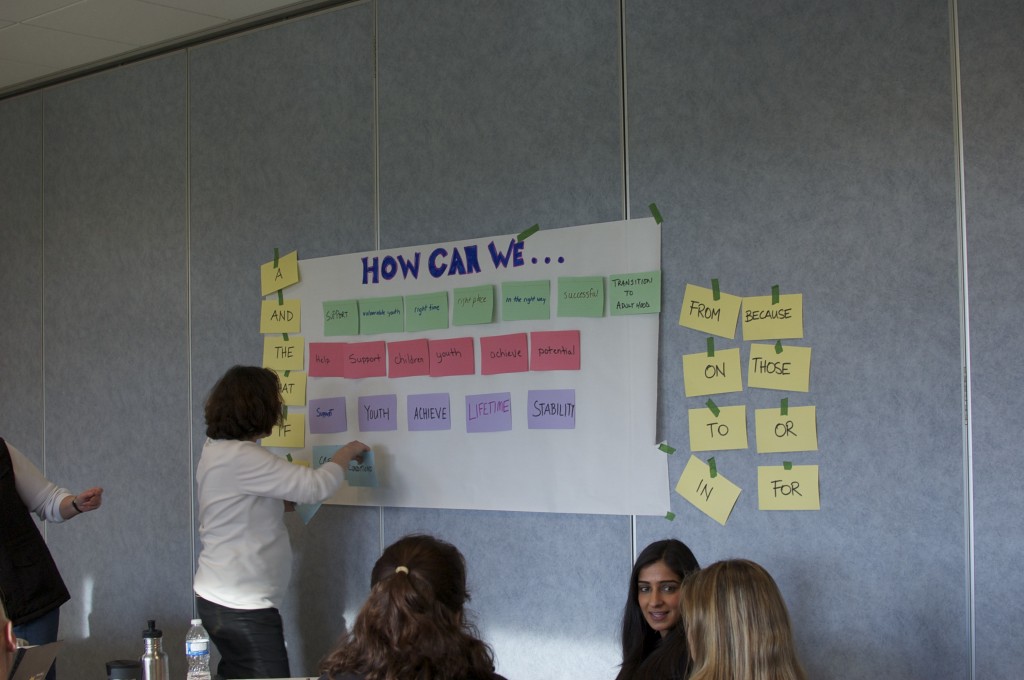

1. The Gallery Walk

What it is: Tables create a poster or flip chart that represents the main points of their discussion and how it relates to the key question under consideration. These posters are put up on a wall and participants stroll past and consider the findings & conclusions.

During their stroll, they engage with others in discussion about what they are seeing, what common themes or threads do they observe, how does the work of other groups complement or diverge from what was heard in other groups. When participants return to their seats, the whole group discussion focuses on identifying the common themes, what was surprising, what the overall conclusions appear to be and finally, what action steps would advance the work to the next stage.

What it does: Instead of listening to lengthy verbal reports from a static position, participants get up and move. They break from one type of activity to another – this allows the mind to shift gears and enables individuals to take the time they need to revive themselves and remain productive and creative. Focus is placed on the inter-connections and significance of the group results to the larger question under exploration and facilitates solution development.

2. Shift and Share

What it is: At the end of group work, each team leaves one person behind as a table host. All other participants move to another table of their choosing (as long as there is a chair available for them).

The table host provides a 5-minute overview of the work of the group and their results. Then the “guests” have 5 minutes to discuss what they heard and provide feedback, critiques, and enhancements to what they heard. It is best if the “host” focuses on listing and recording the discussion rather than have actively engaging or challenging the feedback.

After 2 – 3 rounds of presentations and feedback, everyone returns to their home table to hear the feedback and make revisions and modifications to their conclusions. Since most will have had a chance to hear and contribute to a variety of discussions, the final large group discussion can focus on highlights.

This approach works very well when each group is discussing a different topic or aspect of an issue – its great for generating strategies and actions around individual strategic plan goals for example.

What it does: This method generates a lot of alignment between ideas even where everyone does not have the chance to hear or comment on each topic area. It also allows individuals to select the topics they are most interested in critiquing or where they have the most to contribute – thereby maintaining a high degree of engagement in the exercise. Finally, the report out becomes an active dialogue and co-creation exercise rather than a static lecture of results.

3. Rank and Relate

What it is: Groups put a “star” or some form of symbol beside their top three ideas – however they chose to define that. All ideas are listed but this enables a clear identification of the most important points in relation to the topic under discussion.

Once this is done, groups are asked to create an image, picture or symbol that captures the essence of their discussion, how their top points relate to the broader issue under discussion, or, they are invited to answer a next level question such as “What would the implications be if your conclusions were put into practice?” Once this is complete, groups then report out on their top ideas, the meaning of their pictures or the implications of their conclusions.

What it does: Table report out becomes much shorter and focused on tangible outcomes and concrete conclusions rather than recitations of the points discussed. The method re-energizes the groups by shifting from left-brain to right brain activities – there is also usually a lot of laughter and fun to be had.